In 1811 Avogadro put forward a hypothesis that was neglected by his contemporaries for years. Eventually proven correct, this hypothesis became known as Avogadro’s law, a fundamental law of gases.

The contributions of the Italian chemist Amedeo Avogadro (1776–1856) relate to the work of two of his contemporaries, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and John Dalton. Gay-Lussac’s law of combining volumes (1808) stated that when two gases react, the volumes of the reactants and products—if gases—are in whole number ratios. This law tended to support Dalton’s atomic theory, but Dalton rejected Gay-Lussac’s work. Avogadro, however, saw it as the key to a better understanding of molecular constituency.

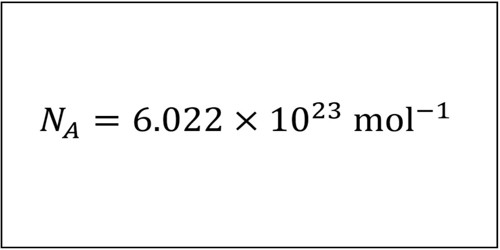

Best known for determining what is known as Avogadro's number. A physical and chemical constant used extensively in chemistry and physics calculations, including those involving gases. His most important accomplishment was research leading to the hypothesis that equal volumes of gas at a given temperature contain the same number of molecules. Amedeo Avogadro was enthralled by science The beginning of the 19th century was an exciting time for chemistry. In the previous two or three decades the age-old myth of phlogiston (a weightless entity given off during combustion) was exploded by Antoine Lavoisier’s recognition of oxygen, and something like a modern list of elements became. Amedeo Avogadro (August 9, 1776–July 9, 1856) was an Italian scientist known for his research on gas volume, pressure, and temperature. He formulated the gas law known as Avogadro's law, which states that all gases, at the same temperature and pressure, have the same number of molecules per volume.

Avogadro’s Hypothesis

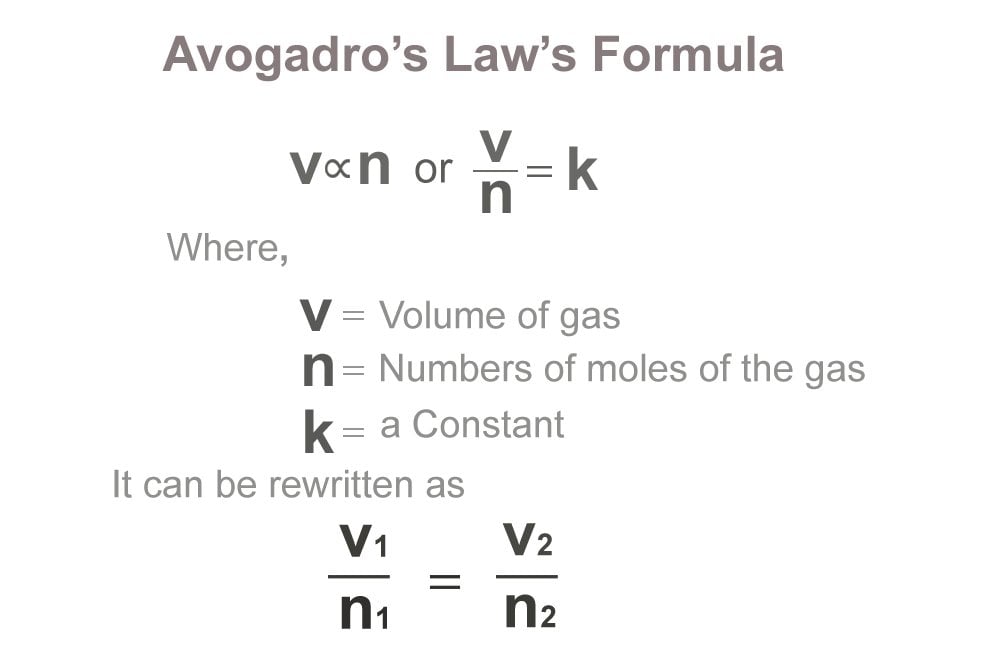

In 1811 Avogadro hypothesized that equal volumes of gases at the same temperature and pressure contain equal numbers of molecules. From this hypothesis it followed that relative molecular weights of any two gases are the same as the ratio of the densities of the two gases under the same conditions of temperature and pressure. Avogadro also astutely reasoned that simple gases were not formed of solitary atoms but were instead compound molecules of two or more atoms. (Avogadro did not actually use the word atom; at the time the words atom and molecule were used almost interchangeably. He talked about three kinds of “molecules,” including an “elementary molecule”—what we would call an atom.) Thus Avogadro was able to overcome the difficulty that Dalton and others had encountered when Gay-Lussac reported that above 100°C the volume of water vapor was twice the volume of the oxygen used to form it. According to Avogadro, the molecule of oxygen had split into two atoms in the course of forming water vapor.

Amedeo Avogadro Law

bio-avogadro.jpg

Edgar Fahs Smith Collection, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania

Amedeo Avogadro Contribution To Chemistry Journal

Curiously, Avogadro’s hypothesis was neglected for half a century after it was first published. Many reasons for this neglect have been cited, including some theoretical problems, such as Jöns Jakob Berzelius’s “dualism,” which asserted that compounds are held together by the attraction of positive and negative electrical charges, making it inconceivable that a molecule composed of two electrically similar atoms—as in oxygen—could exist. In addition, Avogadro was not part of an active community of chemists: the Italy of his day was far from the centers of chemistry in France, Germany, England, and Sweden, where Berzelius was based.

Personal Life

Avogadro was a native of Turin, where his father, Count Filippo Avogadro, was a lawyer and government leader in the Piedmont (Italy was then still divided into independent countries). Avogadro succeeded to his father’s title, earned degrees in law, and began to practice as an ecclesiastical lawyer. After obtaining his formal degrees, he took private lessons in mathematics and sciences, including chemistry. For much of his career as a chemist he held the chair of physical chemistry at the University of Turin.

Amedeo Avogadro Hypothesis

The information contained in this biography was last updated on November 30, 2017.